In C++, managing memory efficiently and safely is a critical skill that can greatly enhance the performance and reliability of your applications. One of the most powerful tools for working with memory is the pointer, a feature unique to low-level languages like C and C++. While pointers offer great flexibility, they also come with complexities and potential pitfalls, such as memory leaks and dangling pointers.

§1 Pointers in C++ #

A pointer is simply a variable that stores a memory address. The syntax for declaring a pointer is:

int* ptr = new int;

Here, ptr is an uninitialized pointer to an integer. The new keyword allocates memory for the pointer.

§1.1 Declaring and Assigning a Pointer #

int a = 10;

int* p = &a; // p is a "pointer" to the address of a

In this case, the pointer p stores the memory address of a. &a gives that address, and *p dereferences to the actual value stored in a.

Note:

int* pint *pint * p

All are all syntactically identical and have the same meaning. The placement of the * when declaring a pointer variable is purely a matter of style and does not change the meaning.

The position of * when dereferencing a pointer can change the meaning.

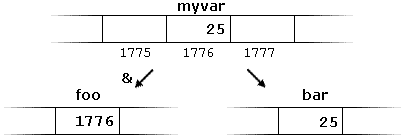

§1.2 Pointer Diagram #

The image on the right depicts the code on the left, with the variable foo being a pointer to the address of myVar, and bar being a copy of myVar. Note how foo is equal to the address of myVar.

int myvar = 25;

int *foo = &myvar;

int bar = myvar;

Diagram sourced from: https://cplusplus.com/doc/tutorial/pointers/

§2 Dereferencing Pointers #

Dereferencing retrieves the value located at the memory address held by the pointer.

To dereference a pointer, use a * symbol next to the pointer variable.

Example:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

int x = 10;

int* ptr = &x; // Pointer to x

std::cout << "Address of x (ptr): " << ptr << std::endl;

std::cout << "Value of x (*ptr): " << *ptr << std::endl; // Dereferencing the pointer

}

ptrstores the address ofx, e.g.0x16dff7320.*ptrdereferences the pointer, giving the value stored at the memory address, which is10.

The output of the above program is:

$ ./test-references

Address of x (ptr): 0x16d3f732c

Value of x (*ptr): 10

§3 Working with Pointers #

When working with pointers, it’s important to always dereference them correctly. C++ allows operations directly on the pointer’s memory address, which is usually not the intended behavior and should be avoided in most cases.

Consider the following simple mistake (comments on the cout lines show the output that line produces):

#include <iostream>

int main() {

int x = 10;

int* ptr = &x; // Pointer to x

std::cout << "Address (ptr): " << ptr << std::endl; // Address (ptr): 0x16ae7f324

std::cout << "Value (*ptr): " << *ptr << std::endl; // Value (*ptr): 10

ptr++; // I meant to add 1 to x

std::cout << "Address (ptr): " << ptr << std::endl; // Address (ptr): 0x16ae7f328

std::cout << "Value (*ptr): " << *ptr << std::endl; // Value (*ptr): 70516816 // WTF?

}

In this example, I added 1 directly to the pointer without dereferencing it first. If you look at the memory address, you’ll notice that it increased by exactly 4, which is the size of an int. When you try to dereference the pointer afterward, the value appears to be some random number. This happens because the pointer is now pointing to a different memory location, and the data there could be anything!

The correct way to work with the pointer:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

int x = 10;

int* ptr = &x; // Pointer to x

std::cout << "Address (ptr): " << ptr << std::endl; // Address (ptr): 0x16af6b32c

std::cout << "Value (*ptr): " << *ptr << std::endl; // Value (*ptr): 10

(*ptr)++; // I am now dereferencing the pointer before adding 1

std::cout << "Address (ptr): " << ptr << std::endl; // Address (ptr): 0x16af6b32c

// notice the address is the same as above

std::cout << "Value (*ptr): " << *ptr << std::endl; // Value (*ptr): 11 // better.

}

The key difference here is that the pointer is dereferenced before performing any operation on it. While parentheses aren’t strictly necessary (since *ptr++ would also work), using them eliminates any confusion about whether the * is a pointer dereference or a multiplication symbol. It also clarifies whether the ++ happens before or after the pointer is dereferenced, making the operation easier to read.

§4 Memory Allocation and Deletion #

Dynamic memory allocation is the concept of allocating memory at runtime, as opposed to compile-time. The new keyword is used to allocate memory, and delete is used to free it.

Example:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main() {

int* ptr = new int; // Dynamically allocate memory for an integer

*ptr = 20; // set the dereferenced value

cout << "Value stored dynamically: " << *ptr << endl; // Value stored dynamically: 20

delete ptr; // Deallocate memory to prevent memory leaks

}

newallocates memory on the heap for an integer.deletefrees the allocated memory.

For arrays, you can allocate a block of memory like this:

int* arr = new int[5]; // Dynamically allocated array

Use delete[] arr; to free a dynamically allocated array.

Forgetting to delete pointers can cause problems; refer to the section on Memory Leaks for more detail.

§5 Memory Leaks #

A memory leak occurs when dynamically allocated memory on the heap is not properly deallocated, leading to wasted memory resources. Over time, memory leaks can exhaust the available memory, causing the program to slow down or crash.

In C++, memory allocated with the new operator needs to be explicitly freed using the delete operator. If delete is not called, the program loses track of the memory, which results in a memory leak. For dynamically allocated arrays, the correct way to free memory is by using delete[].

Example of a Memory Leak:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main() {

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

int* ptr = new int; // Dynamically allocate memory

// Forgetting to call delete results in a memory leak, we lose track of the memory

}

// ... more code here

// "orphaned" memory from the loop is still allocated this whole time

return 0;

}

In this trivial example, memory for the integer is allocated on the heap once every loop iteration, but it is never freed. While the program runs, the memory is still in use and cannot be reclaimed by the system until the program terminates. Over time, repeated memory allocations without proper deallocation will continuously consume more memory. You must always remember to delete your pointers when you no longer need them.

§5.1 Preventing Memory Leaks #

To avoid memory leaks, always free dynamically allocated memory when it’s no longer needed by calling delete or delete[]:

int* ptr = new int(10);

delete ptr; // Properly deallocating the memory

For arrays:

int* arr = new int[5];

delete[] arr; // Correctly deallocating a dynamic array

§6 Null Pointers #

A null pointer is a pointer that points to no valid memory location. It’s used to indicate that the pointer is explicitly not pointing to anything. Both smart pointers and “raw” pointers can be set equal to nullptr.

Example:

int* ptr = nullptr; // Explicitly initializing to null

std::cout << "Address (ptr): " << ptr << std::endl; // Address (ptr): 0x0

std::cout << "Value (*ptr): " << *ptr << std::endl; // segmentation fault

A null pointer will always have a memory address of 0x0 or zero (also referred to as null). A null pointer is not the same as a variable with a 0 value.

A null pointer can never be accessed or dereferenced, since the memory address 0x0 is not accessible by any program.

Attempting to dereference a null pointer will always result in a segmentation fault.

§7 Dangling Pointers #

Dangling pointers are pointers that point to freed memory. Attempting to access a dangling pointer leads to undefined behavior and can cause problems. Avoid this by explicitly setting a pointer to nullptr after deleting the memory.

int *ptr = new int(10); // Dynamically allocate a pointer

delete ptr; // delete the pointer once we are done with it

// the pointer is still pointing to the now deleted memory address...

ptr = nullptr; // set pointer to null so we don't have a pointer to deallocated memory

§8 Void Pointers #

Void pointers are pointers that can reference any type, but cannot be dereferenced without casting.

void* ptr; // create an untyped "void" pointer

double x = 1.1;

ptr = &x;

std::string y = "hello!";

ptr = &y;

int z = 10;

ptr = &z; // `ptr` an hold any value type, but can't be dereferenced directly

int *intPtr = static_cast<int *>(ptr); // cast void pointer to an int pointer

std::cout << *intPtr << std::endl;

Void pointers are dangerous because they hide the variable type, so a wrong cast will cause undefined behavior. Prefer type-safe alternatives such as templates, std::variant, or std::any

§9 Smart Pointers #

Smart pointers are only supported in newer versions of C++. To use them, you must compile your code using a newer compiler standard. The default C++ standard of g++ is typically c++14. You can specify which c++ standard to use with a flag: --std=c++23.

Full example: g++ --std=c++23 -o myProgram main.cpp

Smart pointers help manage memory automatically. They ensure that memory is properly freed when no longer needed, thus preventing memory leaks. They can be found as part of the standard library <memory>.

For example:

#include <iostream>

#include <memory> // smart pointers are part of the <memory> library

using namespace std;

int main() {

unique_ptr<int> ptr = make_unique<int>(10); // Memory managed automatically

// No need to manually delete; the memory is freed when `ptr` goes out of scope

return 0;

}

unique_ptr<int> ptris declaring aunique_pointernamedptrof type integer.make_unique<int>(10)is creating a newunique_ptrinteger and assigning the value10to it.

There are three primary types of smart pointers in C++. all three support automatically deleting themselves when the pointer goes out of scope:

unique_ptr- cannot be copied; ensures that only one pointer can reference the object thatunique_ptrpoints to.

use case: when you want strict ownership and no shared access to a resourceshared_ptr- allows for copies of the pointer to be made; keeps track of how manyshared_ptr’s point to the same object.

use case: when multiple parts of the program need to share ownership of a resource.weak_ptr- special smart pointer that allows for referencing ashared_ptrwithout affecting its reference count.

use case: when you need a temporary, non-owning reference to an object managed by ashared_ptr.

Examples using a unique_ptr and a shared_ptr:

#include <memory>

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main() {

// unique_ptr

unique_ptr<int> ptr = make_unique<int>(42); // Allocates an int

cout << *ptr << endl; // Prints: 42

// int *ptr2 = ptr; // This would cause a compilation error; cannot copy a unique_ptr

// shared_ptr

shared_ptr<int> ptr1 = make_shared<int>(100);

shared_ptr<int> ptr2 = ptr1; // Both ptr1 and ptr2 share ownership

cout << *ptr1 << endl; // Prints: 100

cout << "Use count: " << ptr1.use_count() << endl; // Prints: 2

ptr1.reset(); // ptr1 releases ownership

cout << "Use count after reset: " << ptr2.use_count() << endl; // Prints: 1

}

If necessary, a smart pointer can be converted to a “raw” pointer by using the .get() method:

int* rawPtr = smartPtr.get();

§10 Automatic Garbage Collection #

C++ does not have automatic garbage collection like Java or C#. However, with smart pointers (especially std::shared_ptr), you can achieve a form of automatic memory management. When all references to an object are removed, the memory is automatically deallocated.

This is different from garbage collection because the memory is freed immediately when it is no longer needed, unlike garbage collection, which periodically scans for unused memory at set intervals.

§11 Static vs Dynamic Memory #

- Static Memory (Stack): Automatically managed, fast, scope-bound. Variables are destroyed once they go out of scope. Limited to the stack size.

int x = 10; // Static memory on stack

- Dynamic Memory (Heap): Requires manual management (

new/delete) and is persistent across scopes unless explicitly deleted. Limited by the amount of RAM in the system, which is much larger than the stack.

int* heap_var = new int(5);

delete heap_var; // Manual deletion required

§12 Further Reading #

- The textbook has an entire chapter dedicated to pointers: Chapter 10: Pointers

- Another high-quality tutorial on pointers, with many examples and diagrams: https://cplusplus.com/doc/tutorial/pointers/

§13 Questions #

- In your own words, explain what a pointer is in C++ and why it is useful.

- What problems could arise if you do not

deletepointers? Will this always cause your program to crash?

- What happens if you dereference an uninitialized pointer?

- Explain the purpose of a null pointer and why it is important.

- What is the difference between memory allocated on the stack and memory allocated on the heap? Which is faster?

- What is a memory leak, and what are two ways it can be prevented?

- Explain what a dangling pointer is and how you can avoid it.

- What happens if you use

deletetwice on the same pointer?int* ptr = new int(30); delete ptr; delete ptr; what happens here?

- Describe what smart pointers are and how they are useful.

- How could you allocate a raw array with capacity to hold

90000000(ninety million) integers? Provide the code to accomplish this.

- How do you declare a

unique_ptrnamedfloatPtrthat stores a pointer to the value75.5? (provide a line of code to demonstrate)

- What C++ standard library is

std::shared_ptrincluded in?